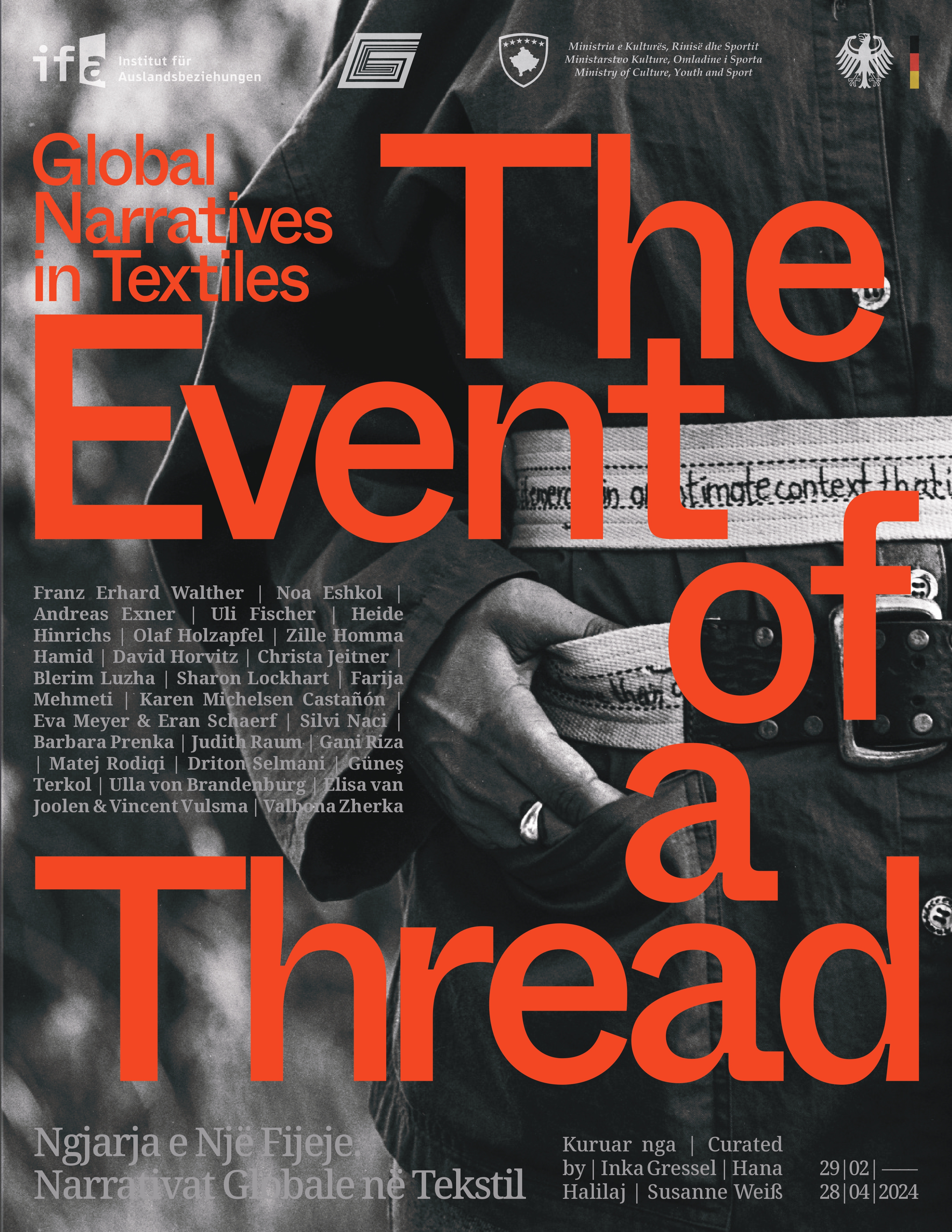

The Event of a Thread. Global Narratives in Textiles

Back and Forth

By Inka Gressel & Susanne Weiß

What information do textiles store? What stories can fabrics tell about their origin, their meaning, their use, their particular material and their immaterial claims? Under which economic conditions and social structures have patterns and formal languages developed over time? How do they change when transferred across cultures? How can artists expand our understanding of textiles? Which techniques do they appropriate, trans- pose and revive?

Textiles have always been a product of technology and a key material of our global economy. The history of trade and the working world resonates within them. Textile crafts are among the oldest of all branches of industry: fabrics reflect changing production conditions and the invisible framework of globalization in its material form. At the same time, they provide insights into local forms of expression, experience and social practice. As such, they are an aesthetic space, capable of adopting patterns and influences from a wide range of sources, constantly outgrowing their boundaries. In this way, they are the physical embodiment of strategies and forms of inclusion, rather than exclusion.

The history of modernity has constantly fluctuated between the mental and technical possibilities of socio- economic modernization and its cultural programs. The Bauhaus, founded in 1919, took the idea of the inter-play between art, craft and industry from the Deutscher Werkbund. Industrialized work processes transformed weaving and its traditionally associated gender roles, whilst mechanical looms restricted physical contact with the material. The Bauhaus textile workshop wanted to recreate the pre-industrial links between art and craft, above all, through the process of working with hand- looms. Art historian T’ai Smith’s work on the history of the Bauhaus textile workshop explores the working relationship between textiles as craft objects and as an art medium. She does not only demonstrate the versatile nature of textiles when used in other disciplines such as painting, architecture and photography, but also reveals internal contradictions of the Bauhaus. Despite the fact arts and crafts were viewed as being interconnected, both categories remained separate and hierarchical. By linking such theory to materials, textures and colors, the Bauhaus weavers were able to develop their own geometric vocabulary. A non-representational verbal language emerged out of the processes and structures surrounding weaving, a language we have come to know through the compositions of weavers from nomadic cultures, for example Persian kilims.

Through study, the Bauhaus artists drew inspiration from the millennia-old craft of weaving. In the 1920s and 1930s, textiles were collected in Germany, notably at Berlin’s Ethnological Museum. They were immortalized in Andean textiles and illustrations, eventually becoming the ideal for the modern eye. For example, the textile designer, weaver and artist Anni Albers dedicated her 1965 book, On Weaving, to the female Andean weavers. She described the woven works of ancient Peru as a crucial medium for an observable vocabulary, owing to the haptic and visual recollection of the weavers. This in turn entwined the profound relationship between individual style and collective memory, nature and culture, technique and sense of belonging. At the same time, these woven objects are the medium for complex traditions and ritual testimony. Weavers translated woven cosmologies into abstract images: “The use of colors and their relation to each other, the emergent rhythm, followed a musical schema, accentuated by complementary contrasts.” In this way, rhythm played a similarly important role at the Bauhaus, alongside theories of perception. The lessons taught by Gertrud Grunow – a musician and one of the Bauhaus “masters of form” – also had considerable influence. Gunta Stölzl, later the head of the textile work- shop, recounted how the completion of a woven piece was celebrated with a large ceremony: the students sat in a circle around the carpet, singing in honor of the finished work. When the Bauhaus moved to Dessau in 1925, the school’s structure changed: less attention was paid to holism, rather a greater emphasis was put on the economic viability of individual workshops. As director, Walter Gropius demanded a fresh union of art and technology. In his eyes, everyone should be capable of creating well-designed objects. This central idea sparked growing interest in the development of products for serial manufacture. Collaboration with industry intensified and the women of the textile workshop developed materials for commercial production, keeping changing modern housing requirements in mind.

The history of the Bauhaus textile workshop plays a particularly significant role in the exhibition. At the request of Elke aus dem Moore, we invited Berlin based artist Judith Raum to closely examine the workshop with the intention of incorporating it into the exhibition. Although the Bauhaus workshop was already extremely well researched, Raum made astonishing discoveries outside of Germany. In six chapters, the installation, titled Bauhaus Space, recounts the workshop’s history, using fabric reproductions and records from important figures such as Gunta Stölzl and Otti Berger, from Weimar and Dessau.

Raum, who always allows economic and social contexts to flow into her paintings, dedicated herself entirely to this part of history. She has created a space that exceeds mere documentation. It encourages the spectators to touch and feel the materials, allowing them to appreciate their artistic qualities. Working in collaboration with architectural duo S.T.I.F.F. and graphic designers Jakob Kirch and Pascal Storz, she has re-realized the structures of the historical weaving mill.

The transcultural back and forth of textiles should not only be understood within the context of the history of the Bauhaus; rather it is inherent to the sources, structure and life of fabrics. One constant is the juxtaposition of craft and industrial practices. Within individual works of art, crucial roles are played by the narrative forms, by the aesthetics and meaning of craftwork, and the working conditions associated with such work. The exhibition’s title – The Event of a Thread – is a quotation from Anni Albers, who included the following outline in the preface to her influential book On Weaving: “Just as it is possible to go from any place to any other, so also, starting from a defined and specialized field, can one arrive at realization of ever-extending relationships. Thus tangential subjects come into view. The thoughts, however, can, I believe, be traced back to the event of a thread.” In her essay “The Event of a Thread,” T’ai Smith reflects on the history and present day of textiles, how they constantly adapt and alter, moving alongside different geopolitical moments. The title of Smith’s article impressed us with its actuality and poetic invocation of the contexts from which such textiles emerge. Without the event – taking place on material, spiritual, visual and economic levels – without an active doing, the thread would remain a single thread, never going on to form a complex construct. So, it is no surprise that context, in linguistic terms, comes from an idea of weaving together. It is the back and forth of image and text that informed the works, what the works narrate, what unifies them, and the way in which they foreground their own narration. The relationships between the individual works change depending on the cultural spaces in which they are viewed. Part of the concept is to engage with local contexts, allowing new narratives to emerge and to be reacted to. During the exhibition’s manifold journey to multiple countries and museums worldwide, other global textile-related stories will be discovered through the cooperation of local co-curators who will weave their own views into the show. We are fascinated by the spatial and temporal back and forth found in the art works –the movement found within and between them.